Session management is a critical area to get right in developing a web application. The developer has to get it right or the entire app is risk of being compromised. Fortunately, the development frameworks have attempted to make this an implementation issue rather than a development issue. A developer just has to pick the mechanism for session management and implement it properly. However, there is a new kid in town that is being used for session management named JWT. Because it is new and it is more flexible than a randomized session cookie, there is more opportunity to make mistakes in how it is implemented. So let’s take a look at some of these issues.

Session management is a critical area to get right in developing a web application. The developer has to get it right or the entire app is risk of being compromised. Fortunately, the development frameworks have attempted to make this an implementation issue rather than a development issue. A developer just has to pick the mechanism for session management and implement it properly. However, there is a new kid in town that is being used for session management named JWT. Because it is new and it is more flexible than a randomized session cookie, there is more opportunity to make mistakes in how it is implemented. So let’s take a look at some of these issues.

What is JWT?

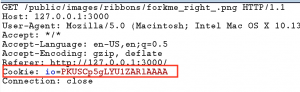

First, let’s take a look at JWT itself. JWT stands for JSON Web Token and is a mechanism for “safely passing claims in space constrained environments.” Space constrained meaning we don’t want to be passing around a ton of data. JWT is defined in an RFC, so it is a It is becoming a popular as an alternative the HTTP cookies that we have come to know over the years. The image below of a cookie in an HTTP request is likely a familiar sight to you.

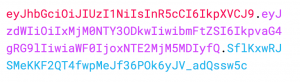

A JWT looks like a very different beast and may throw you off the first time you see it. It looks like a long string of random letters, but it is not random at all. Instead it is a base64 encoded string that is divided into three parts with a period. Below is a JWT while being set in the HTTP response.

What is in a JWT

I mentioned that a JWT is split into three parts using a period previously. The first block is the header, the second is the payload, and the final block is the signature. The header contains the algorithm used and the type of token that it is. Once set, this block will never change within an application.

The second block contains whatever the developer of the application decides to set in the payload. The payload can have pretty much whatever it wants in it. There are some keywords for claims that are reserved for usage by the developer, but they don’t have to be there. Some common claims are IAT (issued at), EXP (expires), SUB (subject) and a host of others. Developers can set their own claims and values for them, as you will see later.

The last block is the signature and is created using a HMAC with a secret key that is stored on the web server. This signature is important, but not required by the JWT RFC. The signature’s function is to provide a check to ensure that the payload has not been modified. The server gets a JWT back with a request and checks it using the HMAC and secret key. If the signatures match, then the payload has not been modified. If it doesn’t match, then the request is invalid and can be discarded.

Enjoying the article?

This is one of the topics that we cover in my web app penetration testing course, Breaking Web App Security. It is something that will be published in an online class and taught live. If you would like to attend the first public session of the course in Salt Lake City on July 26 and 27, 2018, then check out the registration page. This initial class is being offered for $275 with the request for your feedback.

If you would like to be notified of news relating to the class and its online release, then please sign up for my mailing list.

[convertkit form=5048347]JWT Usage

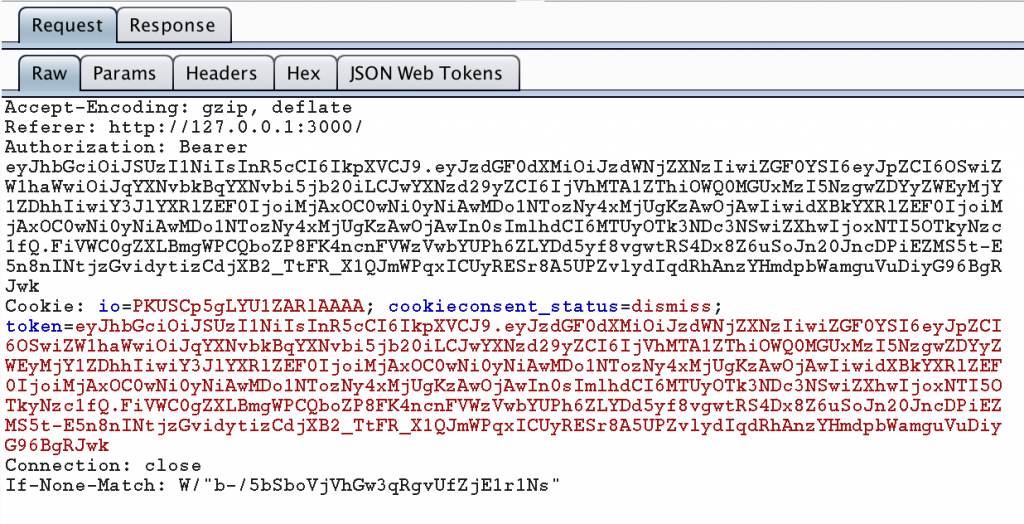

A JWT can be sent on subsequent requests as a cookie or an HTTP Authorization header. I’ve seen it done both ways. In fact, the OWASP Juice Shop uses JWT and sends it both as a header and as a cookie. An example of this is below.

By now you might be wondering what is behind all this base64 encoded text. It is always the first thing that occurs to me whenever I see something encoded like this. Generally, this means that I’m copying from the Proxy tab of Burp Suite over to the Decoder tab so I can see what is going on. The problem here is that our JWT may change quite a bit as I use the app and it would get really annoying to be constantly copying and pasting things.

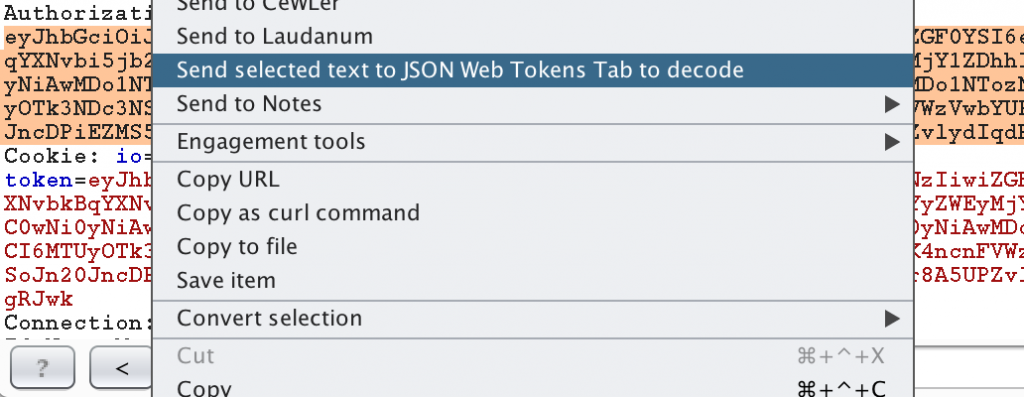

Fortunately, there is a Burp plugin named JSON Web Tokens in the BApp store under the Extender tab. With the plugin installed you can decode a JWT by highlighting it in Burp, right click the highlighted text, and select “Send selected text to JSON Web Tokens tab to decode.”

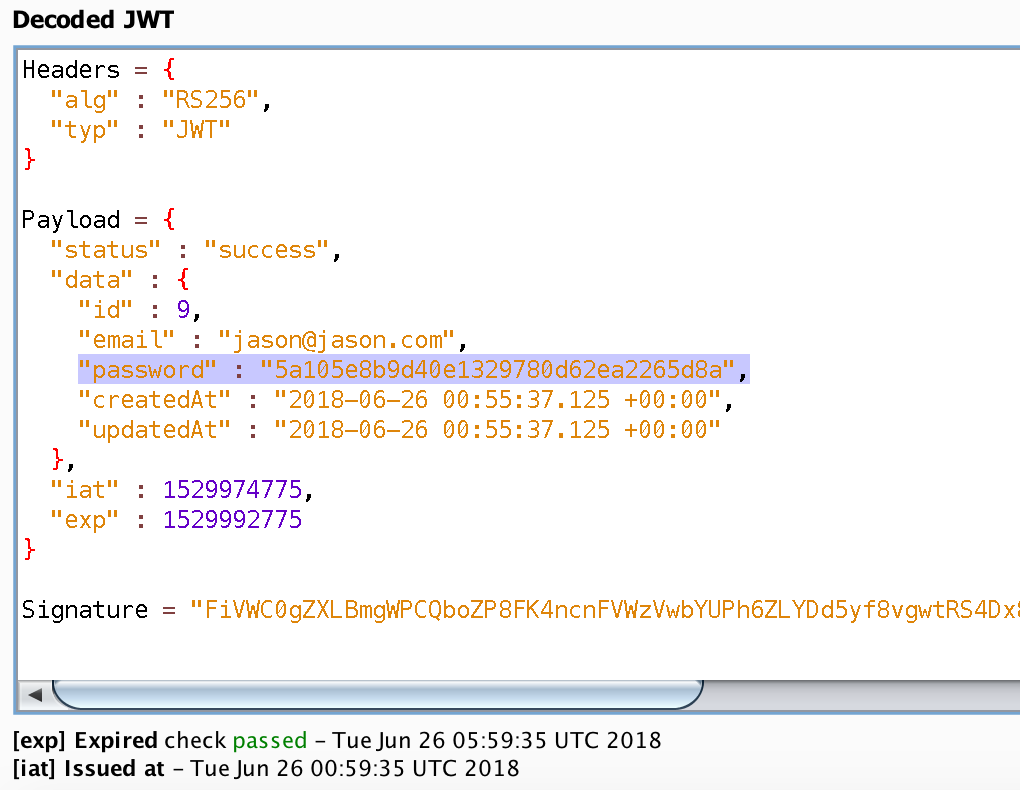

The token is decoded automatically once the JWT has been sent to the JSON Web Tokens tab. There is a text box to enter the secret key for signing the token, but as pen testers we will never have access to the key unless something has gone really wrong for the client. The JSON Web Tokens plugin will automatically find and translate the IAT and EXP claims so that we can see when a token was issued and when it expired. This is very handy since the values that are set in IAT and EXP are the seconds since UNIX epoch. Let’s take a look at a decoded JWT from Juice Shop.

Sensitive Data in JWT

As you are looking at the data contained in this JWT, you are probably noticing some severe issues with it. The first think you probably noticed is that it contains the email address of the user and a hash of the user’s password! This is a terribly implemented JWT because it is putting sensitive data into something that is being used as a session identifier. In this case, Juice Shop uses MD5 as the hashing method for passwords and if you did a search for the hash you would find my super secure password is “test1”. So much for secure password storage and hashing!

This illustrates one of the issues that can (and does) occur with how JWTs are used in applications. There is a temptation to put too much information is put into them. The first time I ran into JWTs in an application was during an architecture review where the client wanted to use them to manage users state. This could include things like who they were, what they were doing in the application and whatever other information a web server would need for the function of the app. They wanted to have highly distributed web servers and didn’t want to have the overhead of checking a user state database.

We have been stating for years that putting user data in cookies is a bad thing to do. The advent of JWT will require us to re-emphasize this practice. Fortunately, the signatures used in JWT makes it possible to prevent the modification of this data. This allows us to be a bit more relaxed on data that is not sensitive. Still, sensitive data has a way of creeping into things like this and it is another point to leak data.

JWT Expiration

Another issue with JWT is the expiration time. We will use the example of my client who wanted to not manage user state. Let’s assume that the signature checks were valid on each JWT and the decentralization planned was implemented. What would happen if a JWT were intercepted and it had an excessively long expiration time? There is no way to force a session using a valid JWT to expire in this decentralized approach. Until the expiration time is reached, there is nothing we can do except potentially play whack-a-mole with the attacker’s IP addresses. It takes the expiration time on cookies and magnifies the issue because there is no where to go to kill a session.

What is an appropriate length of time for a JWT to expire? Obviously it depends on the application. I think it is appropriate to follow the same guidance that we give for session expiration in any application. Some apps are more sensitive than others and have different usage patterns. We accept really long expiration times on sessions to Facebook, but don’t for our banking sites.

JWT Storage

We also need to look at the issues around storage of a JWT. If a JWT is set as a cookie, then all the normal protections browsers provide for cookie storage apply. We want to make sure that the secure flag is set on the cookies to prevent it from being sent unencrypted. We also want to set the HTTPOnly flag so that JavaScript can’t access our JWT. This will prevent a cross site scripting (XSS) vulnerability from exposing our JWT.

However, if we are not storing them as cookies, then where are they being stored? One possibility is to store them in local storage in our browsers. This can be particularly tempting when the user’s state is being packed full of information and put into a JWT. After all, cookies have a limit on their size of 4 KBs. If user state goes beyond that, then the local storage looks very appealing. If that much data is being stored in cookies, then it is likely that the app has a problem with storing sensitive data in the JWT. There is also a problem with the protections (or lack thereof) for local storage.

If local storage is being used for JWTs, then the development team needs to be extremely vigilant on validating user input and using output encoding to avoid XSS vulnerabilities. There are no protections against JavaScript accessing local storage. As soon as an attacker finds an XSS flaw, they can set it to pull the JWTs from local storage and send it to them. The amount of time that they will have access to each victim’s session will depend on the JWT expiration and how fast they can get new sessions.

Wrapping Up

At this point in time I don’t feel that JWT is an inherently bad idea or technology. I do have some reservations on how they get implemented though. If you read the JWT Handbook, you will see that the author has a number of recommendations regarding security. It is still a draft standard and is very new, so I suspect that there will be vulnerabilities that will be found. However, JWT appears to be getting traction in application development and as issues are found they will get fixed. How we implement JWT is really where I see most of the problems being caused. As with most things, it is how we implement them that makes the difference.

- Why Don’t We Hear About Western Cyber-Attacks? - September 17, 2023

- Interview with Carrie Roberts - March 27, 2020

- Interview with Michael Santarcangelo - March 4, 2020